Written by Pendell Meyers, reviewed by Smith, Grauer, McLaren

A woman in her early 30s with history of diabetes had 2-3 days of gradual onset nonradiating chest pain with associated nausea, malaise, and shortness of breath. Then she had an "abrupt change in her mental status and became more somnolent and less responsive" at home in front of her family. Her family called EMS, who found the patient awake and alert complaining of worsening chest pain compared to the prior few days.

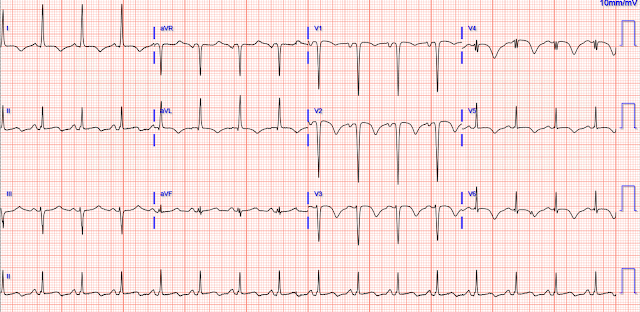

En route to the ED, they recorded this ECG and transmitted it, asking whether the cath lab should be activated:

|

| What do you think? |

There is sinus rhythm at just under 100 bpm. The QRS has high leftward voltage consistent with LVH more than simple healthy young voltage. There is large STE in V1-V3, as well as aVL. There is STD in V5-6, II, III, and aVF. The T waves are questionably hyperacute in V1-V4, but the QRS is also very tall and dramatic. We have very few cases of LVH with large voltage present simultaneously with anterior hyperacute T waves, but the concern is that this could be one of them. A baseline ECG would help greatly (available below).

The subtle LAD OMI vs. normal variant STE formula is not applicable due to the presence of inferior reciprocal STD and lateral STD, and because it was not trained on LVH patients.

If you had erroneously applied the formula, it would be falsely reassuring due to the large QRS voltage present in this case:

A prior baseline was available (though I doubt it was at hand when EMS asked for a prehospital decision on the ECG above):

|

| Baseline (assuming baseline, no clinical info available) from last year. With the baseline (just LVH with some normal variant STE), it is obviously easy to see that the initial ECG above is LAD OMI. Here is her ECG immediately on arrival to the ED: |

Troponin peaked at 23,591 ng/L.

Cardiac MRI done 5 days later:

EF 35%. Severe hypokinesis of the entire septum, anterior wall, and distal/apical segments. No LV thrombus.

Learning Points:

LVH can make OMI interpretation more difficult. It is rare to see high LVH voltage in the same leads as OMI. But this one is an excellent example.

The first troponin is minimal when the benefit of reperfusion is maximal.

Comparison to baseline, and serial ECGs, can make a difficult interpretation easy.

Sudden syncope or "seizure" in sick patients should be assumed to be cardiac arrest until proven otherwise.

Young people and women have OMI, and like other populations they may have delayed recognition.

OMI always evolves on ECG, if you have the ECGs to see it.

Young Women do suffer from thrombotic coronary occlusion!!

- The rhythm is sinus at ~90-95/minute. Intervals (QR, QRS, QTc) and the frontal plane axis are normal (about +20 degrees).

- QRS amplitudes are greatly increased — especially in the chest leads, where there is significant "lead overlap" of complexes.

- There are small and narrow Q waves in lateral leads (I,aVL,V5,V6) — which are almost certain to be normal septal q waves.

- R wave progression is normal (with transition appropriately occurring between leads V2-to-V3).

- Dr. Meyers also emphasized that on occasion — finding a baseline tracing on the patient for comparison can be diagnostic. This was the case with today’s patient — as a quick comparison with the previous ECG left NO doubt that the chest lead ST-T wave peaking in ECG #1 was a new (and therefore acute) finding. Unfortunately, baseline ECGs are not always available at the time they are needed for initial triage decision-making of whether or not to activate the cath lab. So HOW to proceed?

- There are many ECG criteria for the diagnosis of LVH. I list those that I favor in Figure-2 — and discuss in detail my approach to the ECG diagnosis of LVH at THIS LINK.

- Note addition of the patient’s age to the criteria I suggest in Figure-2. The reason for including age — is that younger adults often manifest increased QRS amplitudes on ECG without true chamber LVH. While there is no universally-agreed-upon discrete “maximal age dividing point” — I’ve found ~35 years of age to work well clinically in my experience over decades.

- This number “35” facilitates recall — because, of the 50+ criteria for LVH in the literature — by far the most sensitive and specific criterion in my experience also involves the number “35” (ie, Sum of deepest S in V1 or V2 + tallest R in V5 or V6 ≥35 mm satisfies voltage criteria for LVH in adults ≥35 years of age).

- Assessment of LVH in the pediatric population is problematic — because of the difficulty determining reliable diagnostic voltage criteria for each age group (complicated further by technical issues of ensuring precise chest lead electrode placement in these smaller body frame patients). As a result — I routinely refer to tables for assessing maximal expected amplitudes for each specific age group.

- To “simplify life” when assessing for LVH in younger adults (ie, patients in their late teens, 20s and early 30s) — I’ve found over the years that reversing the number “35” provides a quick “ballpark” assessment criterion as to whether there is sufficient voltage on the ECG of a younger adult (ie, who is under 35yo) to qualify for “LVH” (ie, Sum of deepest S in V1 or V2 + tallest R in V5 or V6 ≥53 mm).

|

Figure-2: Criteria I favor for the ECG diagnosis of LVH. (NOTE: I’ve excerpted this Figure from My Comment at the bottom of the page in the June 20, 2020 post in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog). |

- Note that even accounting for the fact that today’s patient is a younger adult — the 53 mm criterion threshold is attained, suggesting true voltage for LVH in this younger age group patient.

- Remember: The ECG is an imperfect tool to assess LVH. If true chamber size is needed — then an Echo (which also provides information on cardiac function) is far superior to ECG for assessment of chamber enlargement. That said — “pre-ECG interpretation likelihood” for LVH is clearly increased in today’s patient because of longstanding diabetes.

- The patient has LVH on ECG — and as we have mentioned, it is uncommon to see hyperacute anterior T waves in association with marked LVH. Among the types of benign repolarization variants is T wave peaking that is often surprisingly tall in anterior leads in which there are deep S waves.

- There is excellent R wave progression — with an extremely tall R wave in lead V3 (R wave amplitude is typically reduced when there is anterior OMI).

- The QTc is at most no more than minimally prolonged (whereas acute infarction often produces significant QTc prolongation).

- Although the patient in today's case is a young adult — this woman in her 30s has diabetes mellitus (presumably for some period of time) — therefore she clearly is at greater risk of myocardial infarction at an earlier age.

- Even accounting for LVH — the T wave in anterior chest leads is taller than is usually expected. This is especially true in lead V3 — where the 15 mm tall T wave is nearly as tall as the R wave in this lead. The "shape" of LV "strain" when seen in anterior leads tends to be the mirror-image opposite of the slow downslope-faster upslope ST depression typically seen in leads V5,V6 with LVH. It would be unusual to see such a tall, pointed T wave with narrow base from LVH as we see in lead V3.

- Neighboring leads V2 and V4 also appear taller and pointier than is usually seen with either LVH or depolarization variants.

- Finally, while the ST-T wave may normally be negative in lead III when the QRS is predominantly negative — there usually is not the J-point depression seen in Figure-3 (RED arrow in lead III).

- To Emphasize: Once the prior ECG became available for comparison — there no longer was any doubt that the ECG findings highlighted above were acute!

-USE%20copy.png)

-USE.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment

DEAR READER: I have loved receiving your comments, but I am no longer able to moderate them. Since the vast majority are SPAM, I need to moderate them all. Therefore, comments will rarely be published any more. So Sorry.