This middle-aged patient has a remote history of cardiac surgery as a young child for a "heart murmur". Her Apple Watch suddenly told her that she is in atrial fibrillation. She did notice something slightly wrong subjectively, but had no palpitations, chest pain, or SOB, or any other symptom.

Exam was completely normal except for an irregular heart rate.

She was on no medications.

Potassium was normal. Troponin was negative.

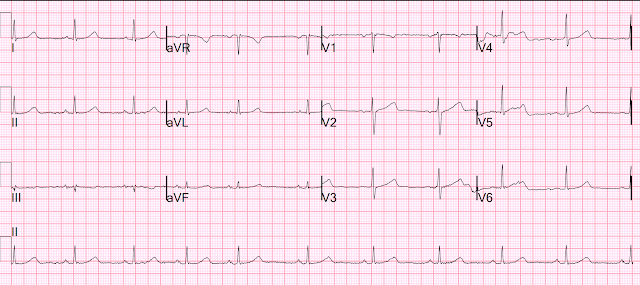

Here is her EKG:

Patients with healthy AV nodes who are not on AV nodal blockers and who are not hyperkalemic should have a rapid ventricular response if they have paroxysmal Atrial fibrillation.

I do not know why she did not have a rapid rate.

But when you see this, you should suspect that the AV node is not well.

Our electrophysiologist told me that highly trained athletes can have such high vagal tone that they do not have a rapid ventricular response.

Her bedside cardiac ultrasound was normal

We decided to cardiovert her since the time of onset was very recent.

I signed her out to one of my partners.

He decided to give ibutilide 1 mg over 10 minutes. Ibutilide can convert atrial fib, or if the atrial fib is resistant to electrical cardioversion, ibutilide can facilitate electrical cardioversion (see my description of the New England Journal article below).

Here is the ECG after ibutilide:

The QT interval is now much longer, at about 460 ms. It was 390 ms prior to this. This is the effect of ibutilide on the repolarization.

They then successfully electrically cardioverted the patients. Here is the post-cardioversion ECG:

Comment:

I would have attempted cardioversion first and only given ibutilide if electricity did not work. In the study below, almost all patients had serious heart disease and they are less likely to convert with electricity alone. This patient was otherwise healthy and should convert with electricity without any problem. If ibutilide is given, then you need to worry about any complications including long QT.

As Dr. Richard Gray says: "Electricity has the shortest half-life of any treatment we give!!"

So it is safe.

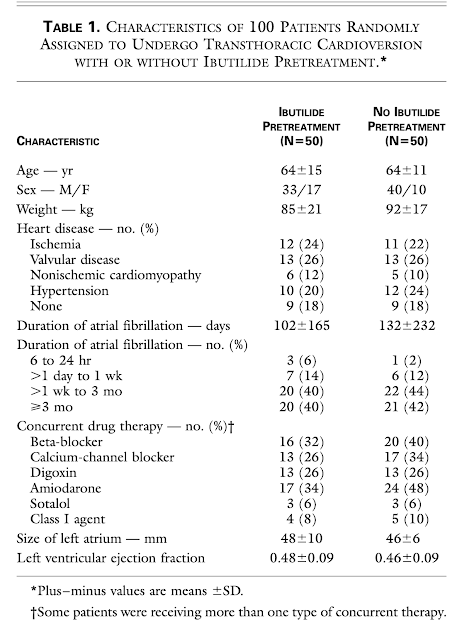

Facilitating Transthoracic Cardioversion of Atrial Fibrillation with Ibutilide Pretreatment. Hakan Oral, New Engl J Med June 17, 1999; 340(24):1849-54.

Abstract

Background. Atrial fibrillation cannot always be converted to sinus rhythm by transthoracic electrical cardioversion. We examined the effect of ibutilide, a class III antiarrhythmic agent, on the energy requirement for atrial defibrillation and assessed the value of this agent in facilitating cardioversion in patients with atrial fibrillation that is resistant to conventional transthoracic cardioversion.

Methods. One hundred patients who had had atrial fibrillation for a mean (±SD) of 117±201 days were randomly assigned to undergo transthoracic cardioversion with or without pretreatment with 1 mg of ibutilide. We designed a step-up protocol in which shocks at 50, 100, 200, 300, and 360 J were used for transthoracic cardioversion. If transthoracic cardioversion was unsuccessful in a patient who had nreceived ibutilide pretreatment, ibutilide was administered and transthoracic cardioversion attempted again.

Results. Conversion to sinus rhythm occurred in 36 of 50 patients who had not received ibutilide (72 percent) and in all 50 patients who had received ibutilide (100 percent, P<0.001). In all 14 patients in whom transthoracic cardioversion alone failed, sinus rhythm was restored when cardioversion was attempted again after the administration of ibutilide. Pretreatment with ibutilide was associated with a reduction in the mean energy required for defibrillation (166±80 J, as compared with 228±93 J without pretreatment; P<0.001). Sustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia occurred in 2 of the 64 patients who received ibutilide (3 percent), both of whom had an ejection fraction of 0.20 or less. The rates of freedom from atrial fibrillation after six months of follow-up were similar in the two randomized groups.

Conclusions. The efficacy of transthoracic cardioversion for converting atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm was enhanced by pretreatment with ibutilide. However, use of this drug should be avoided in patients with very low ejection fractions. (N Engl J Med 1999;340:1849-54.)

Smith comments from the full text: They included patients who had had a fib for less than 48 hours They excluded patients with a fib for longer than 48 hours unless they proved, by TE echo, to not have an atrial thrombus OR unless they anti-coagulated them for 3 weeks first *

Therefore, our patients who have been in afib < 48 hours, or who have been on anticoagulants, apply.

They excluded anyone with a QTc > 480ms because ibutilide can lead to torsades.

The dose was 1mg over 10 minutes

In the 2 patients who went into torsades (both with low ejection fractions, <20%), both were easily controlled.

The authors recommend not using ibutilide for this indication in stable patients if the EF is < 30%. However, it is still an option in unstable patients.

Ibutilide increased the QTc significantly (432+/-37 before vs. 482+/-49 afterward)

Although the point is not discussed in the paper, I would not send such a patient home unless the QT is no longer prolonged.

- I focus my comment on a few additional aspects regarding new AFib.

- The importance of age — activity status — and prior medical history — is the insight this provides into the nature of the AFib that the patient is likely to have.

- NOTE: The data on AFib in younger, athletic individuals that I reviewed (Rao & Calvo studies, above) — was based on the literature, that has been primarily conducted in males. Whether gender-specific differences exist between male and female endurance athletes regarding the occurrence of vagally-mediated AFib is therefore uncertain — and an area of controversy in sports medicine (ie, Some studies suggest vagally-mediated AFib is much more prevalent in male athletes — but lack of adequate data limit conclusions regarding gender prevalence)

- Today’s patient was female. IF it turned out that she was a younger adult extremely active in endurance activities — then increased vagal tone would become a likely contributing factor.

- Other factors may contribute to development of AFib in younger, athletic adults. These include inflammatory changes in the heart (from intense endurance training — which over time, may ultimately lead to some amount of fibrosis) — electrolyte disturbance (potentially enhanced by dehydration) — anatomic changes (ie, the “athletic heart” — leading to increases in chamber size with functional adaptations) — and potential arrhythmia activity (especially increased PACs — that of themself, may precipitate AFib episodes). The above said — the role of increased vagal tone is often a predominant factor in the genesis of AFib in younger athletic individuals.

- Clinically — The importance of factoring in increased vagal tone as a contributing factor to AFib episodes — extends into management. Vagally-mediated AFib is more likely to occur at night or after meals — and less likely to occur with exercise. Baseline bradycardia in endurance athletes limits the use of ß-blockers. As a result — the “pill-in-the-pocket” approach for treatment of episodes (ie, with a Class 1C drug) — is often recommended in athletes with episodic AFib (ie, PAF = Paroxysmal AFib). Alternatively — Disopyramide is sometimes tried (this being a Class IA drug with an anticholinergic effect that may work in some athletes by attenuating vagally-mediated AFib). Finally, in the athlete who participates in intense endurance training — reducing extremes in training and competition may decrease the frequency and severity of AFib episodes (a personal choice for the athlete to contemplate).

- In contrast to the the influential role of increased vagal tone for inducing and maintaining episodes of slow AFib in younger, physically-active individuals — the presentation of new AFib with a slower-than-expected ventricular response is very different in the older patient.

- Rather than increased vagal tone — SSS (Sick Sinus Syndrome) becomes the predominant cause of new AFib with a slow ventricular response in an older individual.

- To Emphasize: The diagnosis of SSS requires ruling out other cause of inappropriately slow AFib in the older patient. These include: i) Use of rate-slowing medication (ie, ß-blockers, digoxin, verapamil/diltiazem, etc.); ii) Acute or recent infarction or ischemia; iii) Hypothyroidism; iv) Neurologic injury; v) Electrolyte disturbance; and, vi) Sleep apnea. If none of these other factors are present — then the older patient (ie, beyond 60 years of age, or so) with new slow AFib should be presumed to have SSS until proven otherwise.

- For more on SSS — See My Comment at the bottom of the page in the July 5, 2018 post in Dr. Smith’s ECG Blog.

- I found it interesting to compare the long lead II rhythm strips in the 3 serial tracings from today’s case (Figure-1).

- More than simply representing a slower-than-expected ventricular response to AFib — I thought there was “group beating” in ECG #1 (ie, fairly similar 3-beat groupings — each separated by a similar, slightly longer pause). While possible that this represents underlying complete AV block with Wenckebach conduction out of a junctional escape pacemaker — the frequency of this unusual arrhythmia has greatly decreased in recent years with reduced use of Digoxin. I therefore thought the significance of this finding in today’s case was uncertain.

- Note that any semblance of group beating is gone in ECG #2 (which shows the obvious irregularity irregularity characteristic of AFib).

- ECG #3: Sinus rhythm has been restored following cardioversion (ie, upright P waves in this lead II now clearly seen). Note fairly marked irregularity of the R-R interval — indicative of definite sinus arrhythmia.

- Application to Today’s Case: A definite correlation exists between sinus arrhythmia and fluctuations in vagal tone (Soos — Stat Pearls: Sinus Arrhythmia — Nov. 25, 2022). The presence of a fairly marked sinus arrhythmia in ECG #3 after conversion to a sinus mechanism suggests that increased vagal tone may indeed have been implicated in today’s case (and perhaps the group beating in ECG #1 during AFib conveyed a similar implication?).

-USE.png) |

| Figure-1: I’ve put together the long lead II rhythm strips from the 3 serial ECGs done in today’s case. What about the regularity (or lack thereof) in these 3 tracings? |

- Not commonly appreciated is the surprising number of AFib patients who do not have symptoms with some (or all) of their episodes. (Ballatore et al — Medicina (Kaunas) 55(8): 497, 2019 — and — Page et al — Circulation 107:1141-1145, 2003).

- An estimated 10-to-40% of all patients with AFib do not have symptoms associated with this arrhythmia. Up to half of the entire AFib burden is among patients with intermittent (or paroxysmal) AFib — and in that population, some Holter studies have shown the majority of PAF episodes are not associated with symptoms. As might be imagined — data collection and drawing conclusions about cardiac and cerebrovascular risk is problematic in this large group of patients with primarily asymptomatic AFib.

- How Does this Relate to Today's Case? — Todday's patient presented with AFib in the absence of chest pain, dyspnea or palpitations. Instead — the reason this woman presented to medical attention, was that she subjectively noted "something was wrong" — and then saw an abnormal rhythm when she looked at her Apple Watch.

- Although reasonable to assume that her subjective feeling that “something was wrong” may indeed have marked the onset of her 1st episode of “new” AFib — the data by Ballatore and Page (links to these references cited above) suggest that it is equally possible today’s patient may have been having asymptomatic episodes of “silent AFib” for some period of time. I suspect that the presentation in today’s case may convey different predictive implications regarding true onset of this patient’s arrhythmia — compared to a patient who awakens from the abrupt onset of palpitations from AFib associated with the usual rapid ventricular response — for whom the likelihood of this truly being the onset of their “1st episode” would seem much higher.

- Editorial NOTE: I’ve questioned if the overall benefit derived from “Apple Watch Monitoring” by patients outweighed potential detriments. Potential drawbacks of patient arrhythmia monitoring — are that Apple Watch detection is less accurate for assessing atrial activity (LA-RA contact with the Apple Watch results in monitoring a Lead I connection — instead of a lead II connection in which P waves would be better seen). My main concern about Apple Watch monitoring — is the potential for increasing the anxiety of otherwise well individuals who become overly focused on, “What terrible arrhythmia is my Apple Watch now showing at this particular moment?” That said — today’s case provides an excellent illustration of when Apple Watch Monitoring did provide an important service for arrhythmia detection.

No comments:

Post a Comment

DEAR READER: I have loved receiving your comments, but I am no longer able to moderate them. Since the vast majority are SPAM, I need to moderate them all. Therefore, comments will rarely be published any more. So Sorry.