|

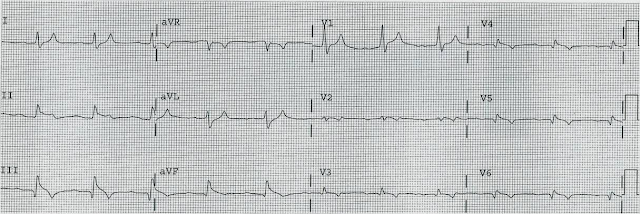

| The above ECG was originally recorded with a paper speed of 50mm/sec. It has been "compressed" on the X-axis so that it looks like it was recorded with a paper speed of 25mm/sec. |

- As Dr Smith has pointed out numerous times on this blog, the ECG is a great tool to assess myocardial viability. Denying patients the potential benefit of revascularization just because their symptoms have lasted a certain amount of time shows poor understanding of the pathophysiology of myocardial ischemia.

- Patients may have repeated episodes of transient reperfusion preventing the myocardium from undergoing necrosis. Also, some patients have enough collateral blood flow that will keep the myocardium viable.

- The ECG, clinical history and echo together should guide the decision on whether or not the patient should go to the cath lab.

- Persistently positive (upright) T-waves 48 hours after AMI onset.

- Premature, gradual reversal of inverted T waves to positive (upright) deflections by 48 to 72 hours after MI onset in the presence of well formed Q-waves.

|

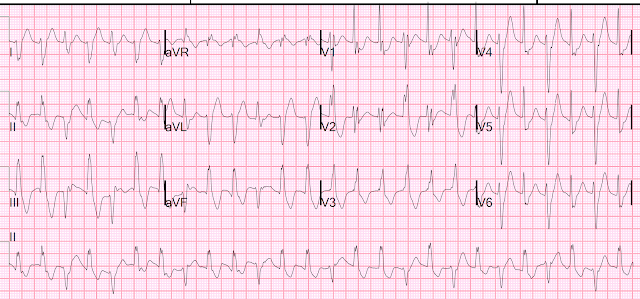

| Above I have reproduced a still frame image from the bed side echo done on this patient. The top of the image is closest to the echo probe. The apex of the heart is at the top of the image with the base at the bottom. The heart chamber are annotated. (RA = right atrium. RV = right ventricle. LA = left atrium. LV =left ventricle. IVS = interventricular septum.) |

- QS-waves with persistent ST Elevation and/or hyperacute T-waves may be due to either Acute MI or to Subacute completed MI with post-infarction pericarditis.

- Postinfarction Pericarditis implies complete transmural infarction and puts the patient at risk for ventricular septal rupture or even free wall myocardial rupture.

- Mechanical complications of transmural infarction are rare and dreaded sequela and have high morbidity and mortality.

- New onset harsh systolic murmur in a patient with subacute completed MI is VSR or papillary muscle rupture (with acute mitral regurgitation) until proven otherwise.

- Post infarction regional pericarditis (PIRP) can be suspected from the ECG and is associated with an increased risk of myocardial rupture.

- Clinical correlation must always be sought before decision making.

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (2/26/2025):

- The fact that although serious complications from acute MI are far less common than in years past — today's case manifests a "combination" of post-infarct complications (ie, post-MI pericarditis; post-MI VSR = Ventricular Septal Rupture). Awareness of the course of these complications is important to facilitate earlier detection.

- This patient's MI was in large part "silent" — in that CP (Chest Pain) was not a prominant complaint. Instead, the patient's primary symptom was severe dyspnea (See the September 5, 2024 post in Dr. Smith's ECG Blog regarding the frequency of "silent" MI, especially in older patients who present with acute dyspnea — with that Sept. 5 case also from Dr. Nossen, and also associated with post-MI VSR).

- Physical Exam was revealing. Most of the time with acute MI — little additional information is provided by physical examination (with exception of those acute MI patients who present with heart failure or shock). Today's patient presented with a harsh, holosystolic murmur consistent with acute VSR. This was detected on admission through the ED (Emergency Department) — but we are not provided with information as to whether a murmur was detected 4 days earlier when the patient was seen in an ambulatory care center and treated with antibiotics for pneumonia. This is relevant — as knowing when the murmur appeared may have expedited realization of VSR in this elderly patient with dementia and severe dyspnea.

- We are not told if a pericardial friction rub was listened for. This could have been another clue for facilitating earlier recognition of tihs patient's post-event pericarditis.

- Point of care Echo was diagnostic — showing obvious regional wall motion abnormality of the distal septum and ventricular apex. Once again, earlier use of Echo would have expedited recognition of the cause of this patient's dyspnea that began 6 days earlier.

- Finally — No ECG was apparently done 4 days earlier at the time of the primary care visit. I learned by subsequent history that this initial encounter was a home visit by a primary care provider — with assessment clearly challenging because of the patient's dementia. But in the "retrospectoscope" — I find it insightful to look back and contemplate whether the patient should have been sent to the ED for evaluation at that time. This is not in any way a criticism — since we clearly lack details for any judgment. But we learn from cases that don't go as expected (ie, it appears the patient never had pneumonia) — and doing the "hard work" of considering what we might do differently the next time we encounter a similar situation is how we improve as clinicians.

- P.S.: There is no mention of a prior ECG in today's case. Realizing that we are not privy to many of the details in today's case — locating a prior tracing for comparison may have clarified a number of conflicting findings in today's ECG (that I've reproduced and labeled in Figure-1).

- How would you interpret the ECG in Figure-1?

-USE.png) |

| Figure-1: I've labeled the initial ECG in today's case. |

- Because my "ECG brain" has been wired for interpretation of ECGs at the 25 mm/second speed (that is standard in the U.S. and in most of the world) — My routine is to selectively reduce the width of such tracings by 50% to compensate for the 50 mm/second speed routinely used with the Cabrera format. This has been done in Figure-1.

- Outlined in BLUE just above lead V1 — are several ECG grid boxes to facilitate recognizing that the R-R interval in ECG #1 is slightly more than 3 large boxes in duration — corresponding to sinus rhythm at a rate of ~90-95/minute.

- Given globalization of our world — we favor familiarization with different recording formats (For detailed review of the Cabrera Format — Check out My Comment at the bottom of the page in the October 26, 2020 post in Dr. Smith's ECG Blog).

The ECG in Figure-1:

As noted — there is sinus rhythm at ~90-95/minute. The PR interval is normal. The QRS is not wide.

- The QTc appears to be at the upper limit of normal, or borderline prolonged (Using our QTc Calculator described in the January 12, 2025 post — and plugging in a rate of ~95/minute and a measured QT = 370 msec, as seen in leads V3,V4 — we come up with an estimated QTc clearly under 450 msec., or still normal).

- Although mid-precordial S waves are quite deep — voltage criteria for LVH are not quite met (See My Comment in the June 20, 2020 post). Instead, the deep chest lead S waves are probably the result of a lack of opposing forces from extensive anterior infarction.

- Multiple Q waves are seen. Although narrow — Q waves are fairly deep in leads -aVR,II,aVF,III; and in leads V5,V6 (BLUE arrows in these leads).

- There is loss of r wave between leads V2-to-V3 (RED arrows in these leads).

- This is followed by a deep QS wave in lead V4. There is fragmentation near the beginning of S wave downslope (within the dotted BLUE oval in this lead V4).

- Whereas it is hard to know what to make of the relatively narrow diffuse limb lead Q waves — the chest lead findings of "loss of r wave" + fragmented QS in V4 + much deeper-than-expected Q waves in V5,V6 indicate extensive anterior MI at some point in time.

- Simple pericarditis does not manifest infarction Q waves. But Q waves are common with post-infarction pericarditis.

- Remarkable for their similarity — 4 successive limb leads ( = leads -aVR,II,aVF,III ) all show Q waves followed by significant J-point ST elevation. Straightening of the ST segments in each of these leads to "my eye" suggests acuity.

- In the face of these 4 successive limb leads showing ST elevation — My "eye" was drawn to mirror-image opposite ST depression in lead aVL and a distinct flattening of the ST segment in neighboring lead I (within the 2 BLUE rectangles).

- ST elevation is marked in leads V3,V4 (more than 4 mm.). Neighboring leads V5,V6 manifest a lesser degree of ST elevation.

- Simple pericarditis does not manifest the kind of reciprocal ST-T wave changes seen in high-lateral leads I,aVL. But the finding of ST elevation in 8/12 leads, in association with the above noted Q waves is probably most consistent with recent extensive infero-antero-lateral MI, now with post-infarction pericarditis.

- The above said — given the patient's age, co-morbidities, and the decision that he was not a surgical candidate, there was little to do clinically that would alter this patient's guarded outcome.

.png)