Written by Willy Frick

Here is Queen of Hearts interpretation with explainability:

She says OMI with high confidence. She is particularly worried by the inferior HATW with apparent posterior extension suggested by STD maximal in V2.

Version 2 of the Queen of Hearts, which is not yet available publicly, stated that this is a false positive (that is without knowing any history!)

I sent this to Dr. Meyers with no context, and he responded "Something a little weird to me, but I'll just go with OMI if the patient has symptoms with a reasonable pre-test probability of ACS, especially chest pain."

Smith: it is atypical for OMI, but as Pendell says, with high pretest probability you would need to assume OMI. But to my eye it is not diagnostic of OMI. Queen version 1 may be wrong here. Maybe we can get an interpretation from Version 2.

Ten minutes later, repeat ECG was performed.

Again, Queen of Hearts interpretation with explainability:

She again says OMI with high confidence. This time, she sees HATW in V6. It is common for a large, dominant RCA to supply the lateral wall. Shortly after this ECG was obtained, cath lab was activated and the patient underwent emergent angiography. What did they find?

The patient had normal coronary arteries.

In addition, her echocardiogram was normal. What explains this? The answer is that it was predictable based on the history. The patient is a middle aged woman with epilepsy and no other medical history. She had a completely normal day with no complaints and was playing cards with family when she had a generalized tonic clonic seizure lasting 30 minutes, finally terminating with midazolam 10 mg IM per EMS. Upon arrival to the ED, her temperature was 103.2 °F, and her other vital signs were within normal limits. Her ECG changes may be baseline (no prior available), or they may be related to prolonged seizure or anti-epileptic drugs.

Now, forget all of the ECGs in this post along with the Queen's interpretation. Imagine all you knew about the patient was the preceding paragraph. Based on this, what would you say the likelihood of OMI is? You would have to say it is extremely low. If you saw 100 similar patients (i.e., in otherwise normal health presenting with seizure and no other symptoms), it would be surprising if even 1 of them had OMI based on history.

Stated differently, her pre-test probability for OMI is at most 1%. So, what does it mean that the Queen of Hearts sees OMI with high confidence? You might be asking yourself, "Aren't the Queen's sensitivity and specificity exceptionally good?" Yes! They're phenomenal. In the largest published study to date, her sensitivity is 80.6% and her specificity is 93.7%. Her area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.938 which is superb.

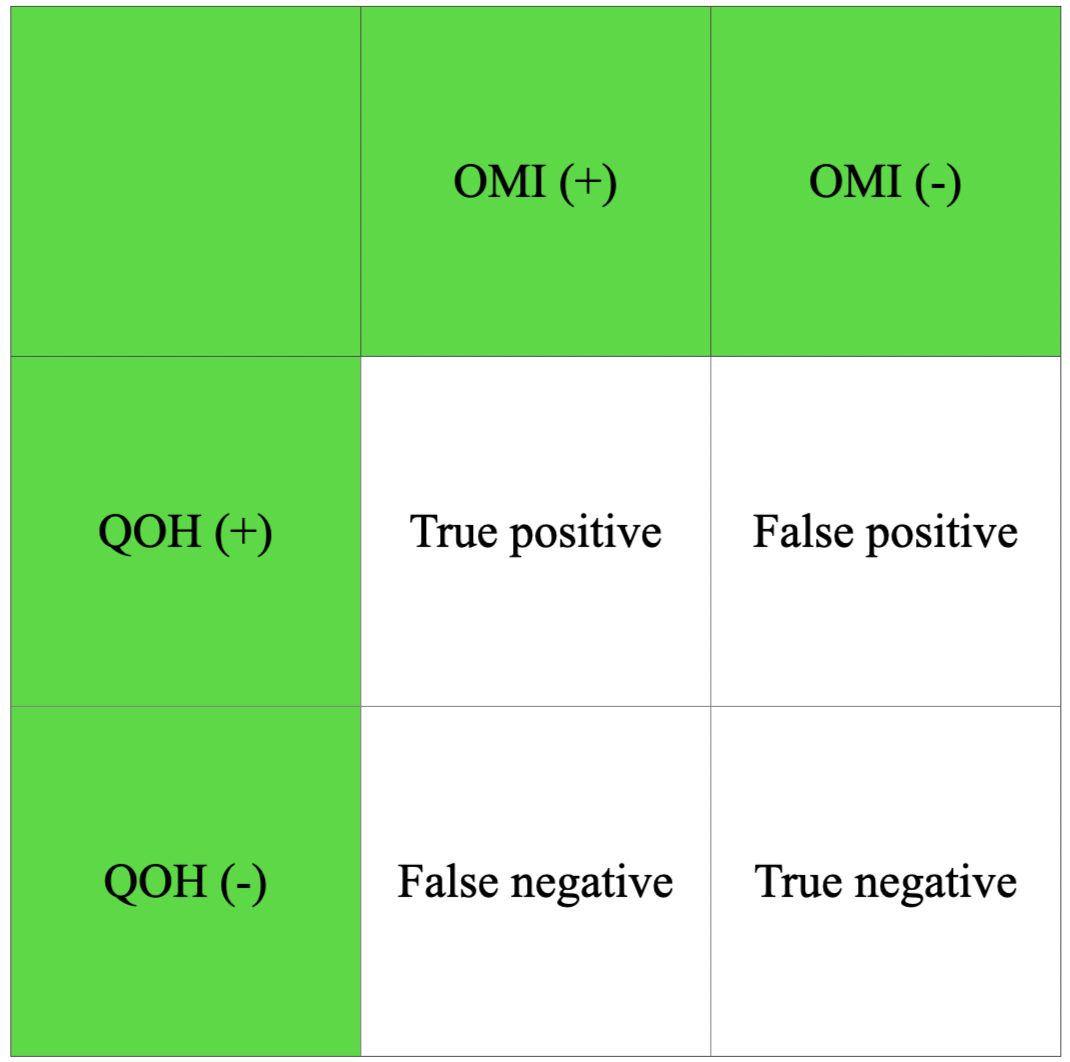

And yet, all of this can be overcome by misapplication of an exceptionally good test in the wrong patient population. Remember the following framework.

Imagine we have 100,000 patients, and 1% of them have OMI. Before reading further, see if you can fill in the numbers in the above grid using these values -- 100,000 patients, 1% incidence of OMI, 80.6% sensitivity, and 93.7% specificity.

If the incidence is 1%, this means 1,000 patients will have OMI, and 99,000 will not have OMI. If the sensitivity of the test (QOH) is 80.6%, then 80.6% of the 1,000 patients with OMI will have a positive test (true positive), and therefore 19.4% of the 1,000 patients with OMI will have a negative test (false negative).

Similarly if the specificity is 93.7%, then 93.7% of the patients without OMI will have a negative test (true negative), and 6.3% will have a positive test (false positive). This is shown below:

Note that the middle column (true positives and false negatives) sums to 1000, and the right column (true negatives and false positives) sums to 99,000. So, back to the question, what does it mean to have a QOH positive ECG in this context?

What you want to know is the positive predictive value of the test. This tells you the likelihood that a positive test represents a true positive (and not a false positive). Test yourself by seeing if you can calculate this number before reading further.

To calculate this number, divide the number of true positives by the number of total positives. In this case, that is:

806/(806 + 6,237) ≈ 11%

In other words, a false positive is much more likely than a true positive. This is why Dr. Meyers said "I'll just go with OMI if the patient has symptoms with a reasonable pretest probability of ACS, especially chest pain."

Learning points:

- ECG is a diagnostic test which must be interpreted in clinical context.

- Estimation of pre-test probability is an essential part of taking good care of patients.

- Diagnostic tests with phenomenal test characteristics perform poorly when they are used in the wrong context.

- The Queen of Hearts was trained on patients presenting to the ED with new onset chest pain, and that is the context in which she performs the best.

Smith comment: the converse is also true: if the pretest probability is very high, a negative test has a low negative predictive value.

Here are more cases related to pretest probability: https://hqmeded-ecg.blogspot.com/search?q=pretest+probability

===================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (7/2/2024):

===================================

Appreciation of the concept conveyed in Dr. Frick's post today — is essential for optimal clinical ECG interpretation.

- In a word — Dr. Frick synthesizes the essence of Bayes' Theorem — which amazingly was first described in 1763 by the English statistician, philosopher and minister, Thomas Bayes.

- In my role as a primary care educator from 1980-2010 — I regularly cited Bayes' Theorem when teaching ETT (Exercise Treadmill Testing) to primary care residents and clinicians.

- Simply stated, as applied to ETT in the office — the likelihood of a patient having coronary disease is proportional to the prevalence (ie, pre-test likelihood) of coronary disease in the population being tested. Viewed from another perspective, "You can't catch any goldfish — if there are no goldfish in the pond."

- Applied to Stress Testing in the office — When the patient in front of me was a middle-aged or older male smoker with classic anginal symptoms on minimal exertion, relieved by rest — I knew before that patient stepped on the treadmill that the likelihood that the ETT would be positive was at least 90%! Realistically, my expectation was less to "confirm" what I already knew (ie, that this patient had coronary disease) — and more to estimate relative severity of his disease (ie, downsloping ST depression within minutes of beginning exercise with reproduction of his angina meant the need for asap cath).

- In contrast — atypical CP (Chest Pain) in a younger woman without significant risk factors meant that even if the ETT resulted in downsloping ST depression — this was more-likely-than-not going to be a false positive test.

What does this have to do with ECGs in the ED?

Practically speaking — the fact that a patient calls EMS or presents to the ED because of new CP automatically places him or her in a higher-risk group for having an acute cardiac event.

- This is not to say that all such patients are having an acute OMI (because we know that is not the case) — but it is to say that the pre-test likelihood for a patient who calls EMS or presents to the ED for new CP is much higher than the pre-test likelihood of acute OMI for a patient who is seen the next day in the office.

- Working in primary care for 30 years — it was rare that we would see a patient with CP come to the office as they were having an acute OMI. I believe there is an intuitive process of self-selection — in that patients who came to the office were much more likely to have some non-cardiac cause of their symptoms — or perhaps angina pectoris in need of evaluation — but they were relatively unlikely to be in the process of having an acute OMI.

BOTTOM Line: As emergency providers — the great majority of patients we encounter who either contact EMS or come to the ED themselves for new CP —automatically fall in a higher-prevalence group with greater likelihood that they are having an acute event.

- Specifics in the history may further increase this risk of an acute cardiac event — but the onus is clearly on us to rule out rather than rule in an acute event — because this patient came to us for new CP.

- That said — the woman in today's case is different from patients who seek our care because of new CP — in that the reason this woman came to the ED was for evaluation of a seizure associated with fever — in the absence of chest pain.

- Conclusion: As per Drs. Frick and Meyers' comments in today's case — the History is of critical importance for optimal clinical ECG interpretation.

- For example — the previously healthy 20-year old with CP, modest troponin elevation, and ECG changes that don't quite fit an anatomic distribution — is far more likely to have acute myocarditis than an acute OMI (far fewer "goldfish" for OMI in that pond).

- In contrast — the older patient with known severe heart disease who presents in a regular WCT (Wide-Complex Tachycardia) rhythm, without clear sign of sinus P waves — has a ~90% likelihood of having VT even before you look at their ECG (Lots of VT "goldfish" in that pond — but very few with aberrant conduction).