Written by Willy Frick

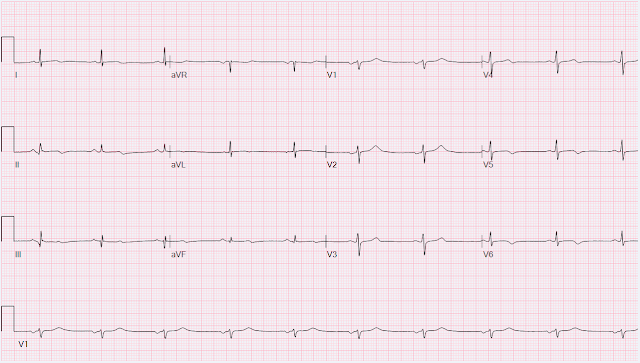

A 46 year old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to urgent care with complaint of "chest burning." The documentation does not describe any additional details of the history. The following ECG was obtained.

The ECG shows sinus bradycardia but is otherwise normal. There is TWI in lead III, but this can be seen in normal ECGs. No labs were obtained. The patient was given a prescription for albuterol and a referral to cardiology.

Smith comment: No patient over 25 years of age with unexplained chest burning should be discharged without a troponin rule out, no matter how normal the ECG. A diagnosis of "reflux" or "GERD" is never supportable without a troponin rule out.

Over the next three days, he continued to have intermittent symptoms and therefore re-presented to the emergency room. He described the symptom as chest burning with occasional radiation into his throat and jaw. He first noticed it while exercising. The day of presentation, the pain woke him from sleep, which is why he decided to come in. The following ECG was obtained around midnight. The machine read was "Normal sinus rhythm, normal ECG."

And Queen of Hearts explainability:

On the combined basis of angiography and IVUS, this patient received stents to his mid RCA, proximal PDA, and OM. While he was in lab, repeat hsTnI jumped from 1417 ng/L to above the upper limit of quantification 60,000 ng/L.

Compared to the prior tracing, we now see:

What do you think?

Algorithm: GE VU 360

Here is the Queen of Hearts interpretation together with lead-by-lead explainability.

She sees OMI with high confidence.

I sent this ECG to Dr. Smith with no clinical context, and he said "posterolateral OMI." Just like the Queen of Hearts, Dr. Smith did not have access to the patient's prior ECG at the time. Here are a few selected leads shown side by side:

We can appreciate the following changes:

- Increase in the area under the curve of the T waves in II and aVF as well as V4-V6

- Newly symmetric T waves in the same leads compared to the prior tracing (which showed a more gradual up slope and more abrupt down slope)

- Similar changes in the T waves in V1-2, but inverted (as would be expected in posterior OMI)

- T wave flattening in V3

- Subtle STE in II, aVF, V4-V6 not meeting STEMI criteria

- STD in V1-2

- Relative STD in V3 (slight physiologic elevation before, now almost isoelectric)

The clinician seeing the patient documented "Sinus arrhythmia with a ventricular rate of 71 bpm. Additional findings: No ST elevation." They also documented "Reproducible chest tenderness." (Remember, reproducible chest tenderness should not reassure you in patients with high pre-test probability of OMI. Our patient already has an ECG diagnostic for OMI, so this finding is useless.) HsTnI drawn at that time was 9 ng/L (ref. < 35 ng/L). Repeat hsTnI 2 hours later was 13 ng/L, a slight increase but still within normal limits.

Smith comment: this is an otherwise healthy relatively young man. It is unlikely, though not at all impossible, that he would have a detectable troponin. Moreover, an change in troponin ≥ 3 leaves a substantial possibility that subsequent troponins will climb higher. This is the Abbott hs troponin and you can only rule out MI with 99% NPV if the first trop, drawn at least 3 hours after pain onset, is <5 ng/L or the delta is < 3 ng/L.

The patient was given aspirin 324 mg and morphine 4 mg IV. (Morphine does not treat myocardial ischemia but does hide it!) Bedside echocardiogram is described as having "grossly normal systolic function." Due to ongoing symptoms, the patient was given a second dose of morphine 4 mg IV. Repeat ECG is shown below.

ECG 3

And here is Queen of Hearts analysis:

Notice the Queen really sees that reciprocal ST depression in aVL

It is not known how the patient's symptoms compared to presentation. Compared to ECG 2, there is new STD in I/aVL which is reciprocal to the inferior changes. However, there is less symmetry and volume in the T waves which suggests that the occlusion may be spontaneously reperfusing.

A dose of NTG 0.4 mg SL is not helpful. A third hsTnI 4 hours after the first was 26 ng/L, still within normal limits. The patient has now had three high sensitivity troponins over the course of four hours that were within normal limits.

Smith comments on these troponins:

Nevertheless, a change in troponin of this magnitude is far beyond both biological variability and the coefficient of variation. See paragraph below for discussion of coefficient of variation. The definition of a high sensitivity troponin assay is really high precision: it can measure the level in at least 50% of normal individuals (levels below the 99th percentile reference) with a minimum coefficient of variation of 10% (high precision) at the 99th percentile.

As for biological variability, the maximum is about 80% from day to day (MUCH less from hour to hour). In other words, if you measure someone's troponin one day, and then the next, the largest change should be no more than 80%. Here the first change was from 9 to 13. This is too much for laboratory variation. But the difference is possible for biologicial variability. So it neither rules out myocardial injury, nor rules it out. However, the 2nd change is from 13 to 26 ng/L. This would be too great a change even from day to day (> 80%) and definitely too much for hour to hour. So there is probability of myocardial injury here (and because it is in the correct clinical setting, then myocardial infarction.) However, the Definition of MI requires at least one value above the 99th percentile, which for a male is 34 ng/L (16 ng/L for women). Thus, the patient does not (yet) get a formal diagnosis of MI and must be called unstable angina unless further troponins return above the 99th percentile.

One must also contend with the coefficient of variation of the troponin test. This is a measure of reproducibility of the test for the SAME sample. If you measure twice, will it be the same? For this test it is VERY low (very good) at 4% at the 99th percentile -- 26 ng/L, but it will not be so good at a level of 9 ng/L. Thus, one considers a test result that varies by 2 or less to be the same result.

Thus, these troponins are very concerning for ACS, and subsequent ones will probably be diagnostic of acute MI.

Finally, troponin rises more slowly in patients with a persistently occluded artery. The troponin is trapped in the myocardium that is not being perfused. One can see troponins skyrocket after PCI of an occlusion due to release. So a patient with persistent pain and a low troponin may have a very large MI!

Case continued

Medicine was called for admission. Repeat ECG at around 9 AM is shown below. His symptoms were improving at this time, but this is not particularly helpful since he received a total of 8 mg morphine.

ECG 4

Much improved. Reperfusion.

She sees no OMI with high confidence. As a brief thought experiment, imagine that the patient had waited a few hours to present, and instead this is the first ECG! It could be mistaken for normal, but in fact it is pseudonormal. In fact, all the T waves are more upright than his prior urgent care ECG. Remember that patients with OMI can have normal ECGs! Repeat hsTnI was 183 ng/L, up from 26 ng/L.

Around noon, cardiology was called for evaluation. Repeat ECG at that time is shown. The patient said his chest pain was 4/10, down from 8/10 on presentation.

ECG 5

Repeat hsTnI rose to 1417 ng/L. At this time, despite a normal appearing ECG, cardiology felt that this was a reperfusing OMI. Given ongoing symptoms, they planned immediate cardiac catheterization. Unfortunately, the cath lab was occupied with a complex structural case, so they elected to temporize with tenecteplase. He was also started on continuous heparin and nitroglycerin infusions, and was given metoprolol tartrate 25 mg, captopril 12.5 mg, and clopidogrel 300 mg.

The patient's symptoms did not resolve. A few hours later, he described only mild improvement in his symptoms from 4/10 to 3/10. Repeat ECG is shown below.

ECG 6

It is essentially unchanged from the prior tracing. On the basis of unresolved angina, cardiology decided to perform rescue PCI. His angiogram is shown below.

This is left anterior oblique cranial ("LAO crani"), best to visualize most or all of the RCA. You can identify LAO because the heart is in front of or to the left of the spine.

Here is an annotated still, showing the RCA which bifurcates into the PDA (indicating a right dominant system) and posterolateral (called "PL") branch. There is diffuse disease throughout the RCA with a severe focal lesion at the red arrow. The PDA has a subtotal occlusion very proximally near the bifurcation, indicated by the yellow arrow toward the center of the image.

This is right anterior oblique caudal ("RAO caudal"), best to visualize the LCx and its branches. You can identify RAO because the spine is off the screen to the left (and the heart is to the right of it).

Here we see the LAD, diagonal branches, the LCx, and a large OM. The LCx has diffuse disease (very lumpy, not smooth) with no severe lesions. The OM has a subtotal occlusion indicated by the purple arrow. The proximal LAD has mild disease, but the distal LAD and diagonal branches are not well evaluated in this view.

Finally, this is right anterior oblique cranial ("RAO crani"), best to visualize most of the LAD. Again, the spine is off the screen to the left, and the heart is to the right of it.

Here we see the LAD, diagonal branches, and the distal LCx. The LAD has diffuse disease with a few areas of moderate stenosis but no flow-limiting lesions. The distal LCx is seen, and the OM is not well visualized here.

From angiography, it is not clear what the culprit is. The ECG changes were inferior, posterior, and lateral. Although it is statistically unlikely, multiple plaque ruptures are possible. On intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), the mid RCA plaque was described as "cratered, inflamed, and bulky," and the OM plaque was described as "bulky with evidence of inflammation and probably ulceration." The PDA plaque was also bulky, but was not described as inflamed or ulcerated.

Evidence regarding intervention to non-culprit plaques is mixed and beyond the scope of this blog post. Heitner et al. (DOI:10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.007305), showed that in patients presenting with NSTEMI:

- The infarct related artery is not able to be identified in 37% of patients

- An incorrect artery is identified as the culprit in 31% of patients

- Among patients receiving PCI, 27% got revascularization only to non-culprit arteries

The recent FIRE trial by Biscaglia et al. (conducted in a different patient population) found a benefit to treatment of non-culprit lesions. One wonders whether the benefit might be mediated in part by avoidance of accidentally missing the culprit!

On the combined basis of angiography and IVUS, this patient received stents to his mid RCA, proximal PDA, and OM. While he was in lab, repeat hsTnI jumped from 1417 ng/L to above the upper limit of quantification 60,000 ng/L.

RCA and PDA before and after, arrows indicating stented regions.

OM before and after, arrow indicating stented region.

If his presenting ECG had been identified and treated emergently, his troponin may even have remained within normal limits. One final ECG was obtained the following morning.

ECG 7

And here is Queen of Hearts explainability:

- Reperfusion biphasic T waves in II and aVF (and perhaps slightly in III)

- Reperfusion biphasic or inverted T waves in V4-V6

- Reperfusion overly upright T waves in V1-3 (reciprocal to posterior TWI)

- Perhaps even subtle reperfusion T waves in I and aVL, supporting the involvement of the OM as (at least) a co-culprit

Learning points:

- NEVER give morphine to suspected ACS unless you are providing symptom relief while awaiting emergent catheterization. Medically refractory angina should have immediate angiography, but this only happens 6.4% of the time.

- Troponin can rise very slowly at first, but this should not reassure you that you have time to waste when symptoms and ECG are suggestive of OMI.

- Patients with OMI can have normal ECGs.

- A pharmacoinvasive approach (tPA followed by catheterization) is sometimes the best option even in a PCI center if the patient is unable to undergo timely angiography.

- Reperfusion findings may not manifest obviously and immediately. Sometimes it can take 12 or 24 hours to see ECG evidence of reperfusion.

===================================

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (1/5/2024):

===================================

Superb and thorough discussion by Dr. Frick of today's case! I therefore decided to aim my comment as an editorial lament. We have on many occasions in Dr. Smith's ECG Blog, highlighted the downside of indiscriminate use of morphine in patients who present with new ischemic CP (Chest Pain). Striving for appropriate use of this invaluable, time-honored analgesic medication should be an EASY goal to achieve. The basic facts are these:

- Morphine works. The drug is easily titrated. It is effective in relieving symptoms. And, the drug does provide physiologic benefits for a patient with an acute cardiac event (ie, it helps to relieve anxiety as well as pain — which may decrease activation of autonomic nervous system activity — often resulting in reduced heart rate, blood pressure, venous return and myocardial oxygen demand — Murphy et al: StatPearls, 2023). And, among our chief goals as medical providers — we want to treat pain when this can be safely done!

- The above said — Morphine clearly should not be given until the decision is made to expedite diagnostic and therapeutic cardiac catheterization. This because relief of CP in such patients leads to delayed cath (because it removes one of the major indications for prompt cath).

- But the simple fact that our patient is presenting with new, severe cardiac-sounding CP that is persistent — is of itself, clear indication for prompt diagnostic (and potentially therapeutic) cardiac catheterization.

- We know that even high-sensitivity troponin may not exceed the "normal" range for a period of hours in certain patients with acute coronary occlusion. So it is faulty reasoning to withhold morphine because you are waiting "until" troponin turns positive.

- We also know that initial ECG(s) may be non-diagnostic despite a recent event (ie, IF an acute occlusion spontaneously opens after only a brief period of time — or if the initial ECG is obtained during the "pseudo-normalization" period).

- So — IF medically refractory new, cardiac-sounding CP is a recommended indication for prompt cardiac cath, even if the initial ECG(s) and troponin(s) are normal — Why are interventionists and other front-line providers committing the compound error of — i) Not performing the KEY diagnostic (and therapeutic) intervention which is prompt cardiac cath in these patients that guidelines clearly indicate as recommended? — and, ii) Leaving their patients with continued, severe CP that morphine could relieve?

- What the "BOTTOM Line" Should Be: Providers should appreciate that persistent ischemic CP is among recommended indications for prompt cardiac cath. Delay in performing prompt cath once this indication is satisfied gains nothing — and risks loss of viable myocardium. Additional motivation for expeditiously arriving at the decision to perform prompt cath — is that you can then treat your patient's CP with as much morphine as might be needed, as well as saving significant myocardium by prompt PCI when cath confirms OMI.

-USE.png)

-USE.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment

DEAR READER: I have loved receiving your comments, but I am no longer able to moderate them. Since the vast majority are SPAM, I need to moderate them all. Therefore, comments will rarely be published any more. So Sorry.