Sent by anonymous, written by Pendell Meyers

A woman in her 40s with no known comorbidities presented with acute chest pain radiating to left arm and neck, which started approximately 4 hours prior to arrival. Vitals were reported as within normal limits except for tachycardia.

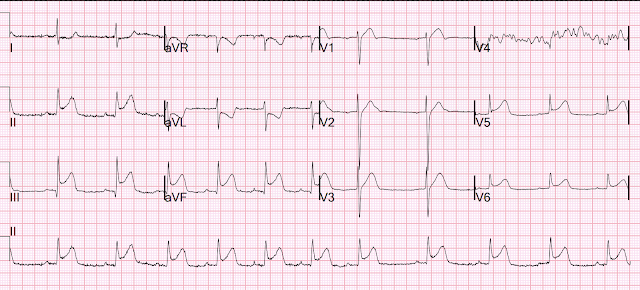

Here is her first ECG on arrival:

|

| Original image. |

|

| PMcardio digitized image. What do you think? |

Side note: I think the rhythm is probably sinus tachycardia, but I can't easily point out the sinus P waves. (See Ken Grauer comment below for further rhythm interpretation on this one!).

|

| Original image. |

|

| PMcardio digitization. |

See some of our many related posts on this deadly pattern:

One of those ECGs you need to instantly recognize, which learners may struggle with at first

Acute chest pain, right bundle branch block, no STEMI criteria, and negative initial troponin.

An elderly woman with acute vomiting, presyncope, and hypotension, and a wide QRS complex

A man in his 40s who really needs you to understand his ECG

Cardiac Arrest at the airport, with an easy but important ECG for everyone to recognize

- The above said — I missed the RA-RL reversal in today's post!

- Medicine is humbling. Just when we think we have "mastered" a clinical entity — we are "brought back to earth" with something we missed. BEST approach is to learn from this.

- I knew that the presence of a flat line in any of the standard leads (I,II,III) — is immediate indication of some type of lead reversal (See My Comment in the October 12, 2024 post). But until now — I did not appreciate that an almost flat line (as in today's post) indicated the same. I now know better.

- As always — my favorite on-line "Quick GO-TO" reference for the most common types of lead reversal comes from LITFL ( = Life-In-The-Fast-Lane). I have used the superb web page they post in their web site on this subject for years. It’s EASY to find — Simply put in, “LITFL Lead Reversal” in the Search bar — and the link comes up instantly.

- Below in Figure-A — is the summary from this LITFL page as to what happens with RA-RL reversal. Unfortunately — there is no way that I know with RA-RL reversal to figure out what today's initial ECG would have shown, had the limb leads been correctly positioned.

- Probably — We would have seen LAHB (Left Anterior HemiBlock) — just as Jose Alencar suspected! This of course makes perfect sense given the "Swirl" pattern from acute proximal LAD occlusion in today's case (ie, RBBB/LAHB is a very common complication of acute proximal LAD OMI! ).

- Possibly — We might have seen sinus P waves. Possibly not. If ECG #1 was sinus tachycardia — I still would have expected to see P waves in some other leads. But unfortunately, we will never know the answer to this — and my point in My Comment below still holds — that we need to always look first at lead II to see if there is or is not an upright P wave.

- Learning Points for Me: An almost flat line in any standard lead may indicate lead reversal. Especially in the presence of an almost flat line — the absence of P waves in lead II (and in all other leads) should prompt us to look again for one of the possible types of lead reversal. Our appreciation to Jose Alencar for his "eagle eye"!

.png) |

| Figure-A: The effects of RA-RL Reversal (as per LITFL — and exactly as pointed out by Jose Alencar and Dr. Smith above). |

MY Comment, by KEN GRAUER, MD (4/15/2025):

- For clarity in Figure-1 — I've reproduced the PMcardio versions of these 2 tracings. To facilitate comparison — I've placed both tracings together in this figure.

- This diagnosis should not have been missed by the Cardiologist on call.

- Fortunately, the ECG was repeated just 15 minutes later (by an astute ED physician) — and the 2nd tracing was correctly identified by the Cardiologist as an acute STEMI, in need of prompt cath.

- Along the way — I believe the initial cardiac rhythm (in ECG #1) was overlooked.

- To Emphasize: Regardless of what the initial cardiac rhythm was — this patient with new CP is in process of evolving an acute LAD OMI that needs prompt reperfusion with PCI (which would probably have fixed the initial rhythm had it persisted). That said — my goal is to offer an additional perspective on some of the more subtle-but-important points manifested by these 2 tracings.

- Warning: What follows is a "deep dive" into the cardiac rhythm of ECG #1. My hope for those who stay with me, is to convey the simple wisdom as to how adding a targeted 5 seconds to your ECG interpretation routine can prevent the rhythm oversight illustrated by today's case.

- If the P wave is not upright in lead II — then you do not have sinus rhythm.

- There are only 2 exceptions to this rule: i) If there is dextrocardia; or, ii) If there is lead reversal.

- While true that on occasion, the P wave with sinus rhythm may be of very low amplitude — there should be a P wave.

- In contrast — No P waves at all are seen in ECG #1. WHITE arrows highlight where we would expect to see sinus P waves if they were present (Note that there is no sign of any P wave in any of the 19 beats in the long lead II rhythm strip).

- Of note — If anything, the PR interval shortens with tachycardia. As a result — IF sinus P waves were present in ECG #1 — they would not be hidden within the preceding ST segment unless there was a very long 1st-degree block (which is highly unlikely given the definite sinus rhythm with normal PR interval in ECG #2 that was recorded just 15 minutes later). Therefore — the rhythm in ECG #1 is not sinus.

- What we do know — is that the rhythm in ECG #1 is regular at a rate of ~115/minute — with a wide QRS (that manifests an RBBB conduction pattern) — but without any sign of atrial activity.

- Regularity of the rhythm rules out AFib.

- Especially given the marked right axis (rS pattern in lead I with predominant negativity) — I considered fascicular VT.

- Narrow initial deflections of the QRS in many leads suggested it more likely that the rhythm was arising from somewhere within the conduction system (ie, junctional tachycardia?; an accelerated His rhythm?).

- Especially given resolution of the RBBB conduction pattern 15 minutes later, at which time heart rate had slowed from ~115/minute to the rate of 95-100/minute seen in ECG #2 — rate-related aberrant conduction of a supraventricular rhythm seemed a good bet. That said — the tiny isoelectric QRS in lead II of ECG #1, and the highly unusual 4-phasic rSR's' morphology in lead V2 are atypical for aberrant conduction.

- Bottom Line: I was not sure of the rhythm diagnosis in ECG #1. My hunch was junctional tachycardia with rate-related aberrant conduction — but regardless of what the rhythm in ECG #1 was, as long as the patient remained hemodynamically stable — prompt cath with PCI was the treatment of choice for both the acute MI as well as the tachycardia.

- Is there an upright P wave with constant PR interval in front of each QRS complex in the long lead II rhythm strip? If not — then the rhythm is not sinus (assuming no lead reversal or dextrocardia).

- With minimal practice — all it takes is 3-to-5 seconds to quickly scan the long lead II. After you do so — you can then turn your attention to the 12-lead.

-USE-USE.png) |

| Figure-1: Comparison between the 2 ECGs in today's case. (To improve visualization — the original ECGs have been digitized using PMcardio). |

- Regardless of what the rhythm in ECG #1 turns out to be — the diagnosis of "Swirl" is secure because there is anterior lead ST elevation that begins in lead V1, with ST segment flattening and depression in lateral chest leads V5,V6.

- With both RBBB conduction and fascicular VT — the abnormal ST segment shape and ST elevation that is clearly present in leads V1,V2,V3 of ECG #1 simply should not be there. (Keep in mind that normally with RBBB conduction — anterior chest leads should show ST-T wave depression and not the elevation that we see here! ).

- The deep and wide Q waves in leads V1 and V3 (and almost in lead V2) — suggest there has already been significant injury.

- Whereas I initially thought the flat line at the end of the long lead II in ECG #2 was the result of some technical mishap (RED question mark) — the presence of what looks to be a P wave occurring just before the standardization marker (BLUE arrows in ECG #2) made me question this initial impression — especially given the acute evolving extensive anteroseptal infarction that minutes earlier in ECG #1 manifested RBBB conduction with marked right axis.

- Bottom Line: While I still suspect this short pause at the end of ECG #2 is the result of some technical mishap — given the clinical situation of extensive anteroseptal MI in progress, close observation of the rhythm to ensure this is not the onset of a Mobitz II block would seem to be in order.

-USE.png)

-USE.png)